"Things in a place they shouldn't be!" A joint exhibition with the EAU History Office

Every urologist has stories of objects inserted into the urethra and bladder, which they have been obliged to remove. This is not, of course, a modern practice.

Every urologist has stories of objects inserted into the urethra and bladder, which they have been obliged to remove. This is not, of course, a modern practice.

In its wonderful collection, the EAU History Office has several instruments that were specifically made to deal with this problem.

They have kindly agreed to share their images of these in this joint exhibition.

Visit the European Museum of Urology

Why do people insert objects into their urethras?

Self treatment

In 1783, General Martin of Lucknow, could stand the pains of his bladder stone no longer and passed a small file into his own bladder several times a day to break it up; it took six months.

The famous 18th century French surgeon, Pierre-Francois Percy (1754 - 1825) described the case of a Cistercian monk who, rather than submitting to lithotomy, passed a chisel through a silver catheter into his bladder and chipped away at his stone. In less than a year, he had filled a small box with fragments.

In 1803, a patient of Dr John Rodman, a man from Paisley with a "serious mental disposition and irritable temper", was suffering from "stricture and gravel". He passed pieces of catgut and a small wire-like catheter to dislodge sandy particles from his bulbar urethra, which allowed him to pass dribbles of urine. After eight months of this, Rodman had to carry out a lithotomy. A further operation in 1805 left him with a perineal urethrostomy through which a file was passed to grind away the stone - it is unclear if the filing was done by patient or surgeon. Sadly the patient died in February 1806 following "excessive drinking of small beer".

In 1872, Mr JB, a 44-year-old draper from Glasgow who had a traumatic perineal fistula and subsequent bladder stone, decided to treat his own stone using a small chisel. After voiding an ounce of fragments he changed his mind and asked a surgeon to finish the job.

In 1872, Mr JB, a 44-year-old draper from Glasgow who had a traumatic perineal fistula and subsequent bladder stone, decided to treat his own stone using a small chisel. After voiding an ounce of fragments he changed his mind and asked a surgeon to finish the job.

Reginald Harrison (pictured right), the 19th century urologist working in the port of Liverpool, was commonly faced with chronic gonococcal urethral strictures in sailors returning from long voyages. Sometimes, attempts had been made aboard ship by a sailor, or another crew member to "treat" the stricture by passing a wire, skewer or piece of whittled wood and even, on one occasion, a piece of lead gas pipe down the urethra.

We still see patients now who, in frustration with their urinary symptoms, pass home-made “dilators” into their urethras.

Iatrogenic

Occasionally, urological instruments and pieces (e,g, fragments of catheters) have to be removed from the bladder or urethra - this occurred in the past as well as now.

Occasionally, urological instruments and pieces (e,g, fragments of catheters) have to be removed from the bladder or urethra - this occurred in the past as well as now.

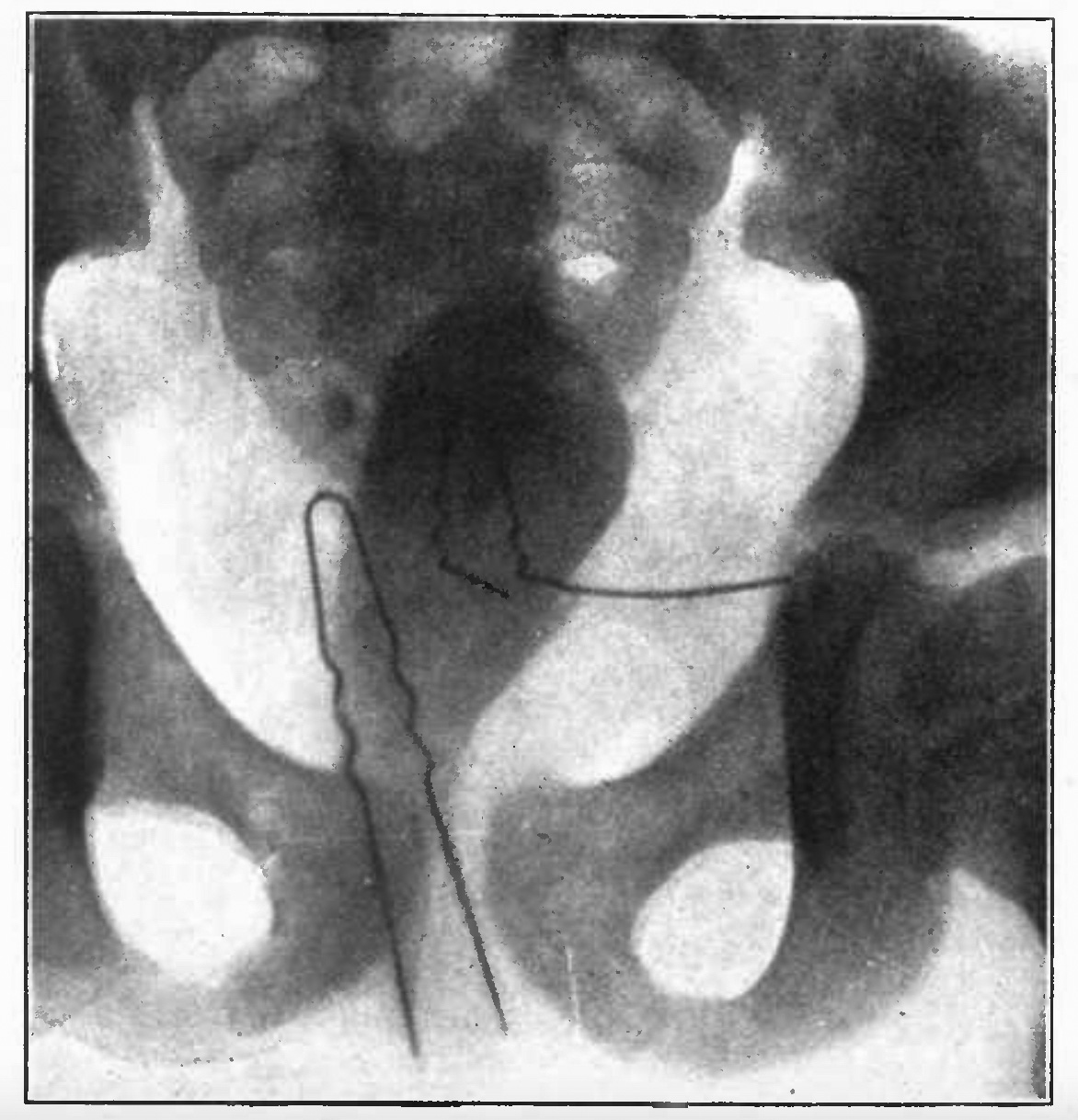

Older rubber catheters and bougies were more brittle, and more likely to fragment. In 1910, Leo Casper wrote that broken-off catheters and bougies were more commonly seen than self-inserted objects. The early x-ray on the right shows a rubber catheter "lost" by a patient some months earlier, only noticed when the x-ray was taken (Modern Urology - Cabot 1918: click the image for a larger, resizeable view).

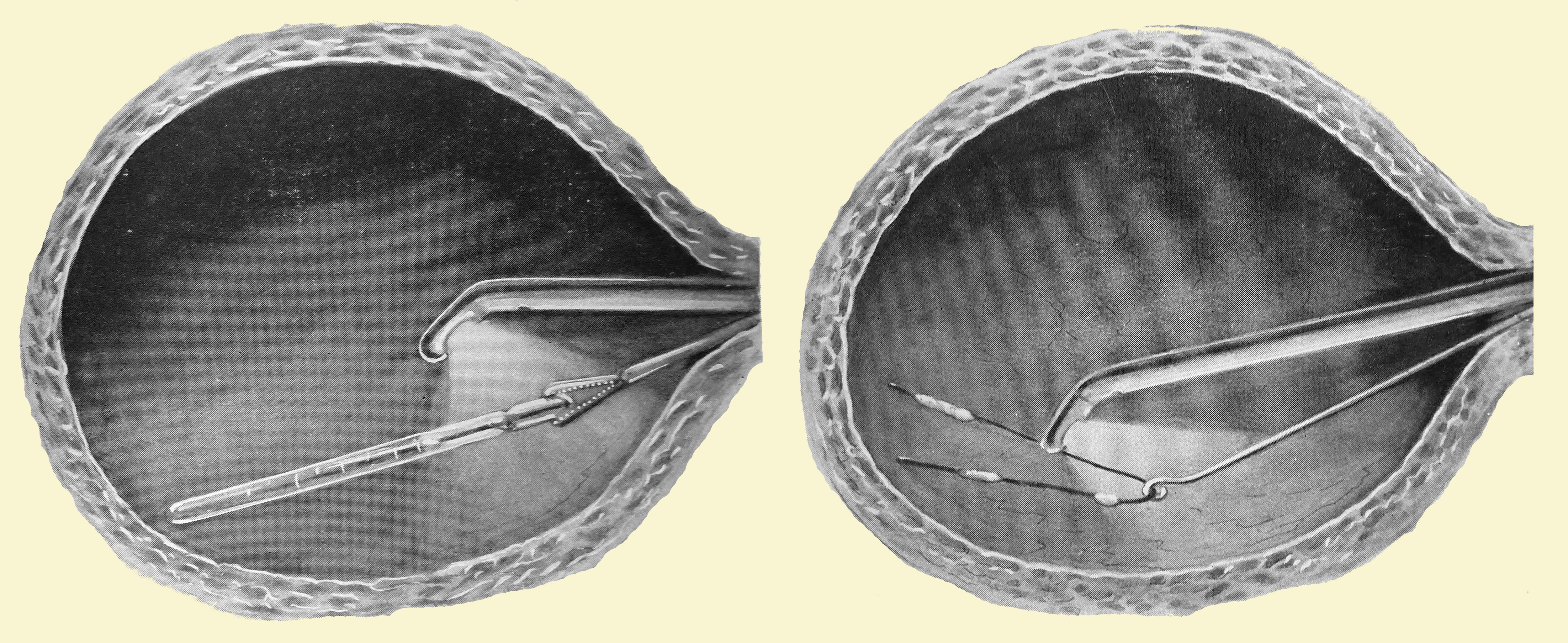

In the second image shown (right), a filiform guide has become disconnected from a Teevan urethrotome and has knotted itself in the bladder. Hurry Fenwick photographed it before removing it with a blind lithotrite (click the image for a larger, resizeable view).

He used the cystosope to visualise the object and then, knowing its postion and lie within the bladder, grasped it by feel.

This took place before the introduction of visual graspers and forceps.

In the images below, Edward Canny Ryall, a pioneering endourologist, demonstrates how to remove a "lost" filliform bougie from the bladder using his cystoscope and grasping forceps (Operative Cystoscopy - Canny Ryall, 1925). Click the image for a larger, full-screen view.

Sexual stimulation

Sometimes the reason was (and is), as Dr Casper stated, “erotic intensions”. Reginald Harrison took a more measured approach saying it was, “for reasons often best known to the patients themselves”. Manipulation of the urethra can, in some, lead to sexual pleasure. The passing of metal or glass rods (often urological dilators) and sometimes fluids, is popularly known as “urethral sounding”.

In 1700, Sir Thomas Molyneux (1661 - 1733) described a case to The Royal Society of a young Irish woman called Dorcas Blake. She had pushed a bodkin into her bladder, although she swore she had swallowed it! It had to be removed by a very early suprapubic cystotomy. Read the account of Dorcas in the Museum Library here.

In 1700, Sir Thomas Molyneux (1661 - 1733) described a case to The Royal Society of a young Irish woman called Dorcas Blake. She had pushed a bodkin into her bladder, although she swore she had swallowed it! It had to be removed by a very early suprapubic cystotomy. Read the account of Dorcas in the Museum Library here.

Hairpins

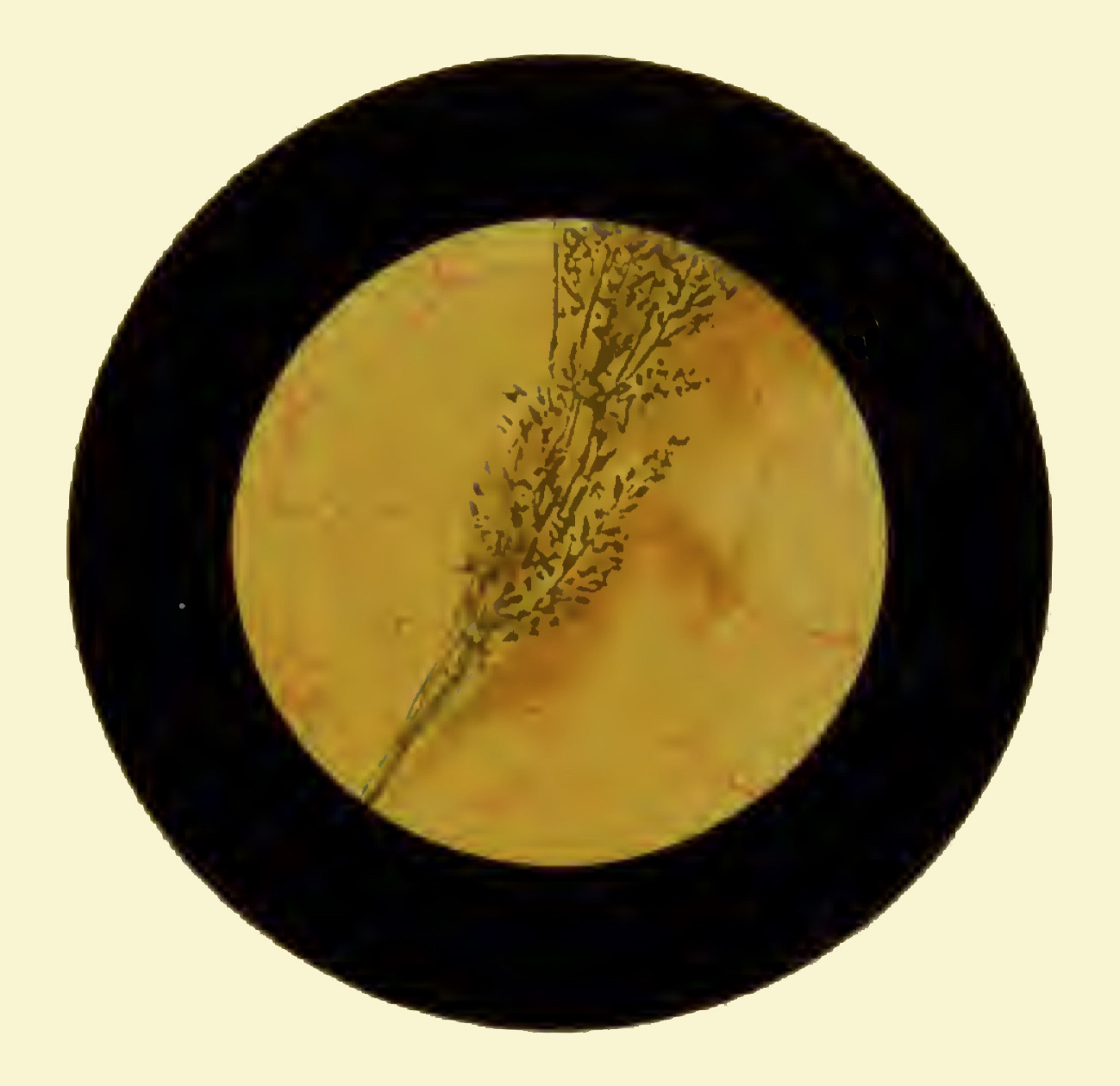

One object frequently passed into the female urethra over time seems to have been the hairpin. The image (right) is a cystoscopic photograph taken by Edwin Hurry Fenwick of the London Hospital, using a Nitze photo-cystoscope. It shows a hairpin in a girl's bladder.

Pictured below is a hook specifically designed by Gentile of Paris for removing hairpins from the female bladder (1905 Catalogue).

Before the invention of the cystoscope, foreign bodies could only be detected by passing blind sounds to feel for the position of the object. The cystoscope made it posible to visualise an object and plan its removal.

Before the invention of the cystoscope, foreign bodies could only be detected by passing blind sounds to feel for the position of the object. The cystoscope made it posible to visualise an object and plan its removal.

The invention of X-rays in 1895 by Wilhelm Röntgen added to the urologist's diagnostic armoury.

Pictured (right) is an X-ray showing two hairpins in the bladder of a young girl (Modern Urology - Cabot 1918: click the image for a larger, resizeable view).

Plant material

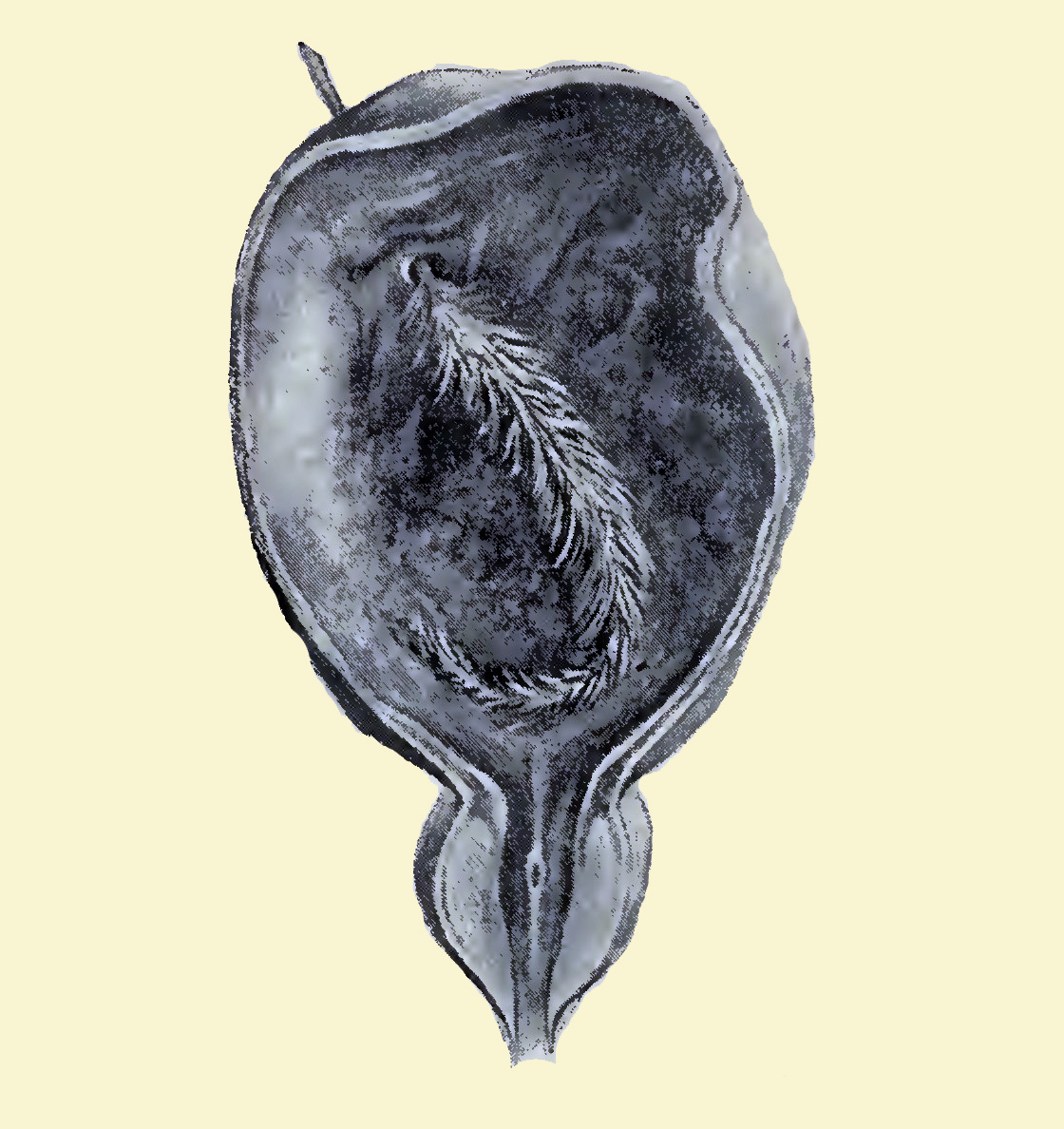

The left of the two images (right) is from a patient admitted to Liverpool Royal Infirmary in 1865. The patient was in the habit of passing differnt materials into his urethra for, as Reginald Harrison wrote, "a supposed stricture".

This piece of grass passed easily into the bladder, but the seeds on the ear prevented its removal. The history was "not obtained without considerable difficulty", the soft object could not be felt by the lithotrite and the patient eventually died of peritonitis.

This piece of grass passed easily into the bladder, but the seeds on the ear prevented its removal. The history was "not obtained without considerable difficulty", the soft object could not be felt by the lithotrite and the patient eventually died of peritonitis.

The right of the two images was also one of Harrison's patients, photographed by Hurry Fenwick down the newly available cystoscope (Atlas of Cystoscopy - Fenwick 1893). Click either image for a larger, re-sizeable view.

Harrison also referred to a third patient from Manchester with a three inch length of sage in the bladder.

Clinical thermometers & more hairpins

The left-hand image (below) is a clinical thermometer being retrieved from the bladder with the aid of a cystoscope and flexible grasping forceps (Operative Cystoscopy - Canny Ryall 1925). Great care is needed when removing a thermometer to avoid breaking it and releasing mercury into the bladder. The right-hand image shows a hook being used to remove another hairpin, with adherent stones, under cystoscopic guidance (Operative Cystoscopy - Canny Ryall 1925). Click the image for a larger, full-screen view.

Other objects

The list of objects found in human bladders is highly varied and, without doubt, most present-day urologists could add to it. Some of the things described in old urology textbooks include: pins, sewing or knitting needles, wires, matches, pencils, feathers, a bulb-headed piece of grass, plastic pens, plastic wire etc.

Instruments from the EAU History Office Collection

Instruments designed for the male bladder

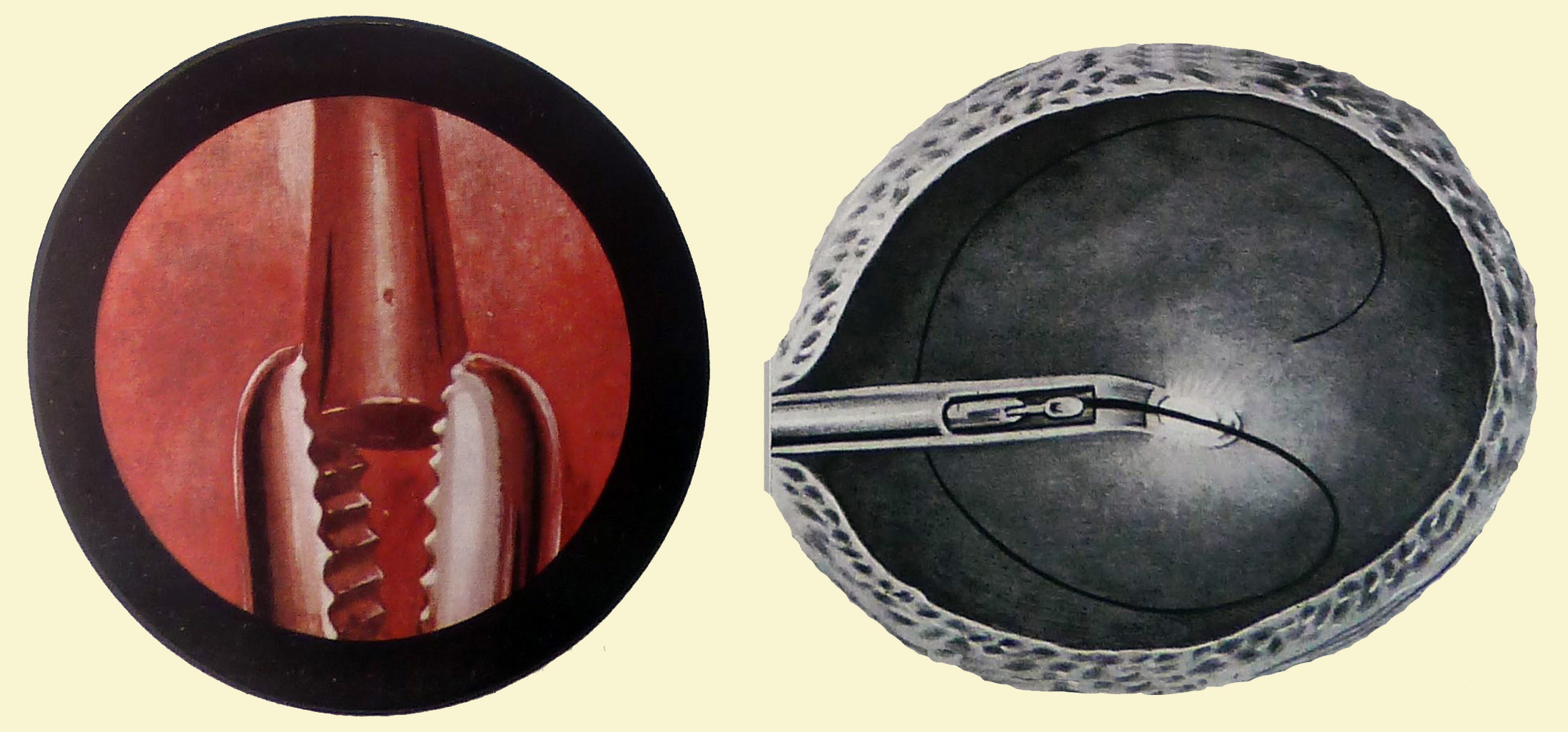

The Collin grasper for men (pictured right) was designed in the late 19th century for removing foreign bodies from the male bladder. Details of its use can be found in the 1925 Collin catalogue.

The Collin grasper for men (pictured right) was designed in the late 19th century for removing foreign bodies from the male bladder. Details of its use can be found in the 1925 Collin catalogue.

The jaws of the grasper are shown separately in the smaller, left-hand image. Click the right-hand image for a larger, full-screen view.

The jaws are shaped so that, when a cylindrical object is grasped, it rotates into them. The central rod can then be used to push the object up the jaws so it can be extracted safely. Click on the image below for a full-screen view of the drawing.

Instruments designed for the female bladder

The Collin grasper for women pictured is also from the the 1925 Collins' catalogue. Click the image for a larger, full-screen view. The foreign body, for example a piece of catheter, is grasped and as the jaws retract, the cylindrical body is aligned with the instrument and can then be safely removed from the bladder.

The Collin grasper for women pictured is also from the the 1925 Collins' catalogue. Click the image for a larger, full-screen view. The foreign body, for example a piece of catheter, is grasped and as the jaws retract, the cylindrical body is aligned with the instrument and can then be safely removed from the bladder.

Click on the image below for a full-screen drawing of this instrument.

Toothed retrieval forceps (pictured below) could be used to extract foreign bodies from the female bladder. This instrument has a central channel through which a wire or stylette can be passed. Click on the image for a full-screen version.

The female urethra can be dilated to allow a small direct vision cystoscope to be passed alongside the forceps to visualise the object to be removed.

Hunter's urethral forceps (pictured below) were useful for extracting objects from the urethra and could also be used in the female bladder. Designed by Alexander Hunter MD of New York, the instrument was first shown in the Tiemann and Co catalogue of 1895. Click on the image for a full-screen version.

Multi-function instruments

The instrument pictured (below) is described as a Mercier's duplicator in Joseph Bryant's Operative Surgery 1899. It can be used for removing wires, catheters and bougies.

It is designed to bend a piece of catheter or a soft wire in two so it can be withdrawn more safely, firmly grasped in the hook. Click on the image for a full-screen version, or here to view the working end of the instrument.

The instrument pictured below is very similar to a Reliquet's urethral lithotrite, again potentially useful for removing foreign bodies as well as stones. Although not exactly the same, a similar instrument can be seen in the Tiemann catalogue of 1879. Click on the image for a full-screen version, or here to vew the working end of the instrument.

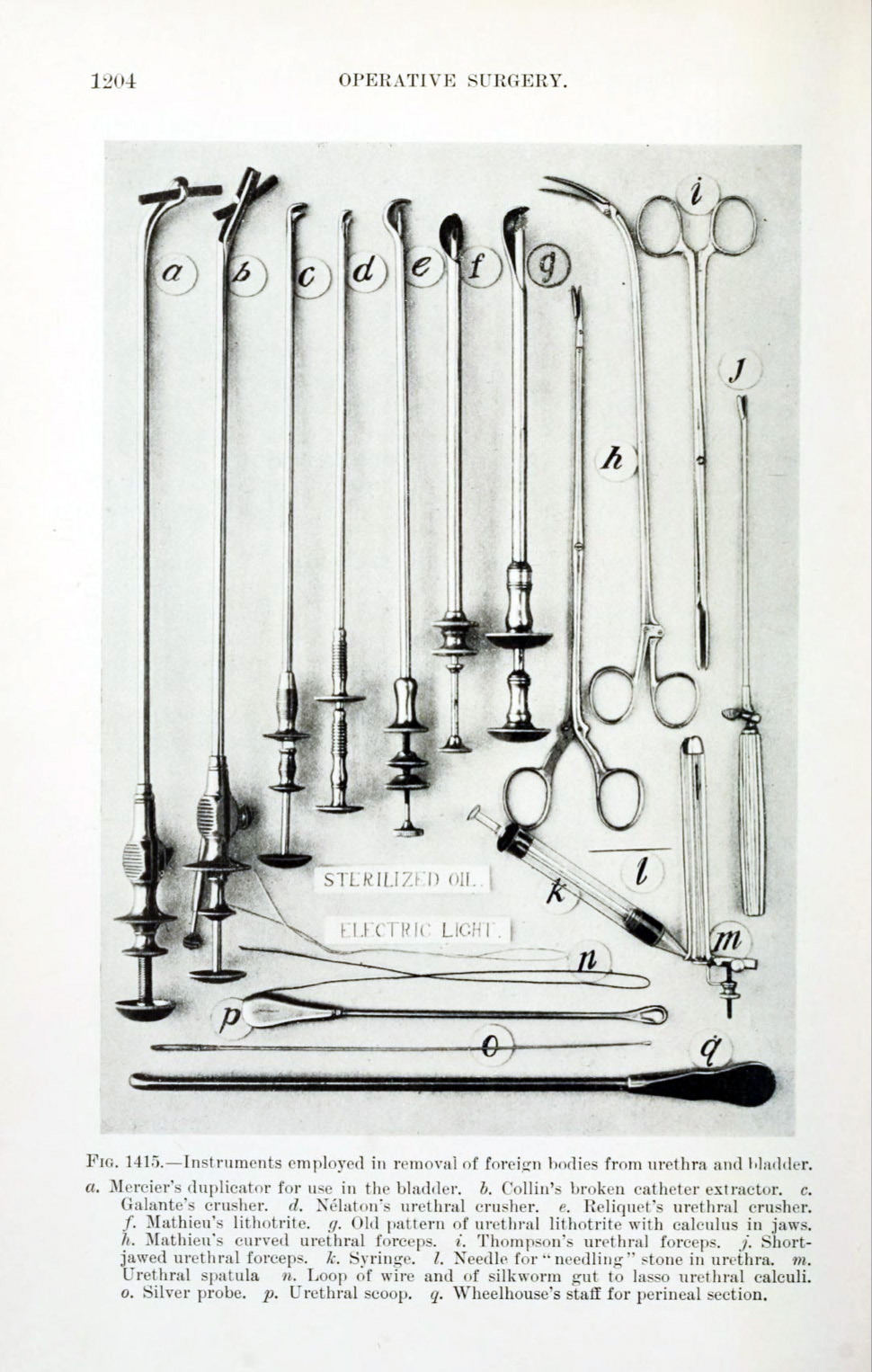

Perhaps a more acurate picture is in Joseph Bryant's Operative Surgery from 1899, where this instrument is described as "Old Pattern of Urethral Lithotrite": the catalogue page is reproduced below.

This is a fine display of instruments used for removing foreign bodies, and includes loops of wire and silkworm gut lassos. Many are dual-purpose, useful for removing stone fragments or foreign bodies. No telescopes are displayed in this instrument set which predates the widespread use of visual endoscopic removal.

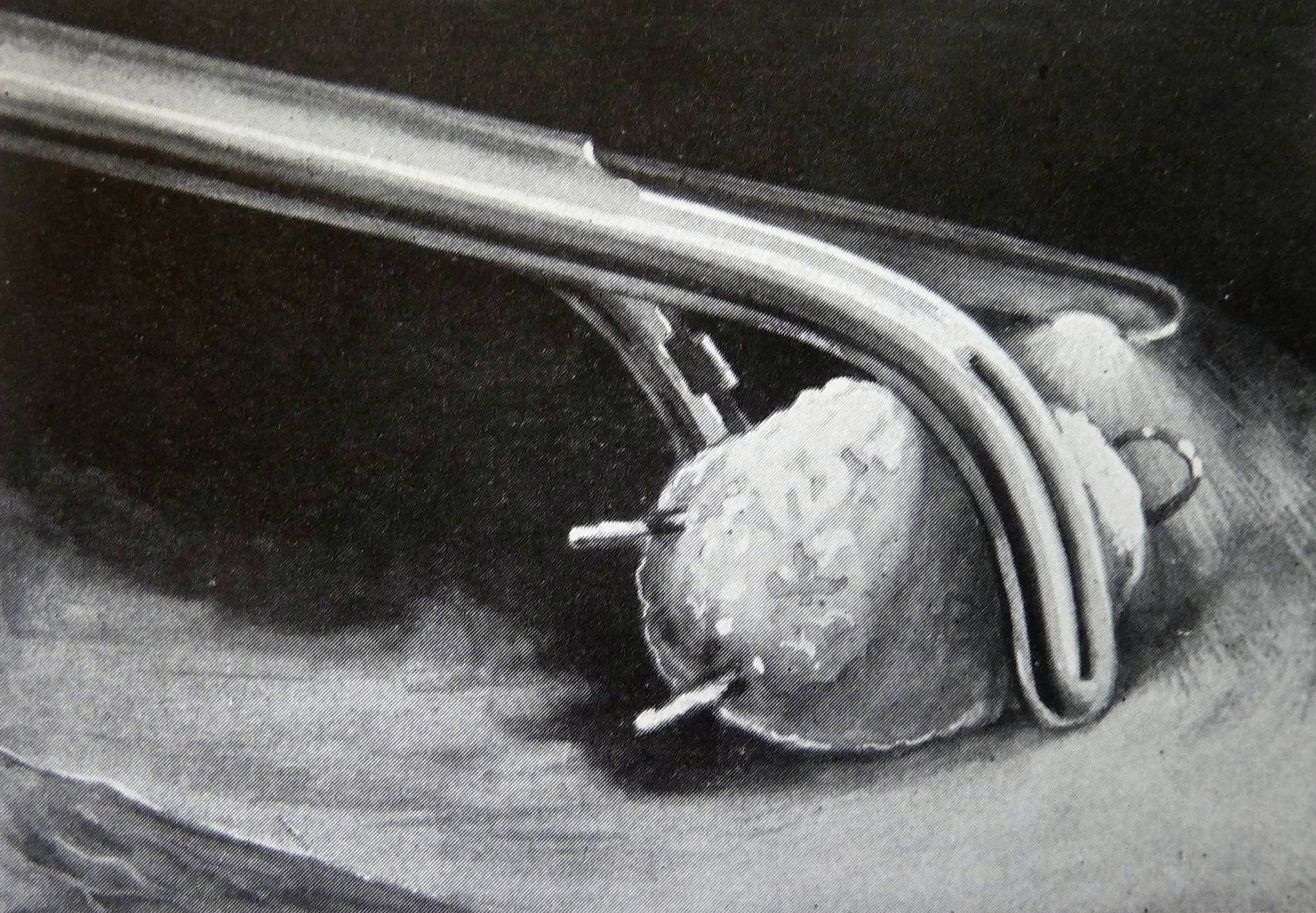

The final image is an illustration of a Canny Ryall lithotrite (Operative Cystoscopy - Canny Ryall 1925) being used to remove a hairpin encrusted with stone under direct vision.

And finally ...

In the words of Prof John Blandy (1976):

The antiques which have been removed from bladders at one time or another would fill a sizable museum ...

BAUS is very grateful to the EAU History Office for the use of these images from their collection.

← Back to Instruments & Equipment Room