What are the symptoms of kidney stones?

Stones are produced from chemicals which have crystallised in concentrated urine; the crystals can enlarge over time (like stalactites or stalagmites in a cave).

The symptoms and signs may include:

- no symptoms - if a stone stays in your kidney, it may not cause any symptoms at all, and may only be found found "by chance" (usually on an X-ray or scan done for another reason);

- aching in your loin (flank);

- non-visible blood in your urine - found only when your urine is examined under a microscope or tested using a sensitive dipstick; or

- infection in your urine - stones are a known risk factor for urinary infection; or

- ureteric colic - severe pain as a stone passes down towards your bladder from your kidney.

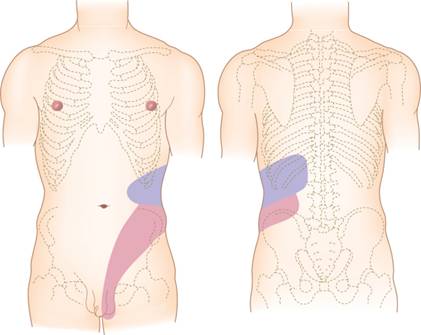

When a stone moves down from your kidney into your ureter (the tube that carries urine from the kidney to the bladder), you may get severe pain (known as ureteric colic). This can be very unpleasant, often with nausea and vomiting. It usually starts in your loin, and may radiate down to your groin or testicle/labia as the stone moves down (pictured right).

When the stone gets close to your bladder, you may get a constant need to pass urine although there is nothing to pass; this is due to the stone irritating the base of your bladder and "fooling" it into thinking that it is full. A stone in this position can also cause:

- burning when you pass urine;

- pain at the tip of your penis or urethra (waterpipe); and

- visible blood in your urine.

What should I do if I think I have stones?

The symptoms above are not specific to kidney stones. Similar symptoms can be caused by problems with your back or spine, and other urological or non-urological conditions. if you have any of these symptoms, you should arrange an appointment with your GP to see what further tests you may need.

Acute ureteric colic often needs urgent referral so that you can get adequate pain relief (which may require injections) and urgent imaging (usually a CT scan). This helps to decide whether your stone can be left to pass by itself, or whether you need admission to hospital. If this is your first stone episode, you may need to visit your local Accident & Emergency Department for pain relief and imaging; this helps to make the diagnosis quickly, and means we can rule out any other cause for your sudden abdominal pain.

What are the facts about kidney stones?

Kidney stones are common. They are a "chance" finding in 8% of patients (one in 12) having a CT scan, and have been steadily increasing in incidence since the early 20th century.

One in 11 people (9%) will get stone symptoms during their lifetime. Men are affected slightly more often than women, with the risk greater in Caucasians than in other ethnic groups. Patients of all ages suffer from stones, but the peak age for a first stone is around the age of 45.

There are several types of stone, grouped according to their biochemical composition:

Calcium-based stones (60 to 80% of all)

Calcium-based stones are the commonest type, and include calcium oxalate stones and calcium phosphate stones. Calcium stones are usually a mixture of both, but are mostly made from calcium oxalate (the commonest stone overall). This is probably because calcium and oxalate/phosphate are very insoluble when mixed together in urine

Struvite stones (10 to 15% of all)

These are also known as “infection” or “triple phosphate” stones (because they are made of calcium, magnesium and ammonium phosphate). They are slightly commoner in women because of their association with urinary infection. Infections with certain bacteria convert urea (a waste product in your urine) into ammonia; this makes your urine alkaline and allows calcium phosphate to crystallise out, so that very large stones can grow, sometimes filling the whole kidney. The largest stones are known as “staghorn” calculi, and these can be the most challenging of all stones to treat.

Uric acid stones (5 to 10% of all)

These tend to have a smooth surface and golden colour. They form in acidic urine and are commoner in people who eat a diet rich in animal protein.

They are also seen in patients with the metabolic syndrome (see below) whose urine tends to be unusually acidic.

Cystine stones (1% of all)

Cystinuria is a hereditary condition caused by a genetic defect. Although rare, it causes stones in young patients. Cystine stones often recur and need multi-disciplinary care, not only to treat the stones, but to help prevent further ones forming (see below). If you have cystinuria, we often recommend that other members of your family are also screened for the disease.

Cystinuria UK website

Others (1% of all)

Other types of stone are rare. Some drugs can cause crystals to form in your urine which then grow into stones. This is sometimes seen with triamterene (a diuretic) or indinavir (an anti-HIV drug). Very rarely, stones may form from xanthine crystals, due to an inherited enzyme deficiency.

What are the risk factors for stone formation?

Your body gets rid of unwanted chemicals through your kidneys; they are filtered out of your bloodstream and passed into your urine but, under certain conditions, they can crystallise in your urine and develop into a stone.

Stone formation occurs if:

- there is an excess of certain chemicals in your urine;

- there is a lack of other chemicals in your urine that prevent crystallisation; and

- your urine volume is not enough to prevent the chemicals from crystallising.

This means that all stone-formers should drink plenty of fluid (particularly water), so that their urine is dilute and the risk of crystallisation and stone formation is reduced.

Stone formation is governed by both intrinsic (e.g. heredity, age & sex) and extrinsic factors (e.g. geography, climate, water intake & diet). A diet high in animal protein, that contains a lot of refined sugar and salt, increases the risk of forming stones, particularly when combined with a poor fluid intake.

Some patients have anatomical abnormalities affecting the structure and drainage of their kidneys; some of these increase the risk of stone formation. They can usually be seen on scans, and need to be factored into decision-making for any active treatment. Sometimes, these abnormalities need surgical correction at the same time as stone treatment.

Stones are also associated with the "metabolic syndrome" (see below). The insulin resistance, which is part of the syndrome, affects the way that your kidneys control the acidity of your urine, so your urine tends to be acidic, increasing the risk of uric acid stone formation; it also makes you more likely to develop diabetes.

It is unusual for stone-formers to have a single factor causing their stone(s); it is more likely that a combination of the factors above is involved.

Patients who have already had a stone have a greater risk of another stone later in life. As a general rule, if you have had a stone, there is a 50% chance that you will form another one within the next 10 years.

What should I expect when I visit my GP?

Your GP should work through a recommended scheme of assessment for suspected kidney stones. This may include one or all of the following:

1. A full history

Your GP will will take a full clinical history to try to work out whether your symptoms are due to kidney stones. At the same time, he/she will make additional enquiries about your general health, to find out if your symptoms are better explained by an alternative condition, or if there is anything else of importance that needs to be investigated as a priority.

As far as kidney stones are concerned, you should expect to be asked about your diet, time spent in a hot dry climate, your fluid intake and whether there is a family history of stones

2. A physical examination

A full physical examination, including assessment of your abdomen, will usually be performed and your blood pressure may be taken as part of the assessment.

3. Additional tests

Your GP may then arrange some tests to assess the likelihood of stones and to exclude another cause for your symptoms.

a. General blood tests

It is common to measure overall kidney function, blood sugar, and to make additional general checks on your blood for anaemia or other problems. As far as stones are concerned, measuring the level of calcium, phosphate and uric acid is useful to see if raised levels are potentially linked to the formation of kidney stones. The actual tests performed will, of course, be at your GP's discretion.

b. Urine tests

Your urine will usually be tested with a special dipstick for blood (most patients with a stone have a trace of blood in their urine) and pH (acidity). If there are white blood cells or nitrites found on the test, especially if the history suggests symptoms of infection, your GP may arrange for a urine sample to be sent to the laboratory for see if there are any bacteria present.

c. Other specific tests

The best way to diagnose stones is to have some imaging. Depending on your GP’s assessment, either a urinary tract ultrasound or a CT scan may be suggested. The advantage of ultrasound is that it does not require X-rays, so it can be used as a first-line investigation in anyone. If you do have a stone, your GP may then refer you to a urologist to discuss the implications and treatment options (see below).

What should I expect if I see a urologist?

Most patients referred to a urologist have been seen by their GP or in an Accident & Emergency Department; they have usually had a urinary tract ultrasound or a CT scan which has confirmed a stone. For the occasional patient who has not had any form of imaging, a CT scan will usually be arranged as the investigation of choice.

1. Imaging with CT

CT not only confirms the diagnosis, but gives additional information about your stone that will help you and your urologist decide the best course of management. The CT is done wiithout an injection of contrast medium (dye), and looks at the whole of your urinary tract (kidneys, ureters and bladder). It shows the site of your stone, and whether there is more than one. It also shows stone size; this is an important factor in choosing the best treatment.

We can also estimate that “hardness” of your stone from CT; this is useful in choosing the correct treatment (e.g. shockwave lithotripsy is better for "softer" stones).

2. Stone analysis

If you have passed a stone (or fragments of stone after treatment) we usually do a biochemical analysis on it. This helps us provide you with specific advice about preventing further stone formation. It may also trigger a “metabolic stone screen” if the stone has a particular composition (e.g. cystine or pure calcium phosphate).

3. Metabolic stone screen

At least one 24-hour urine collection may be recommended to analyse your urine in detail. This is not needed in everyone, but is usually done if you have one of the risk factors below:

- you were young (less than 30 years old) when you formed your first stone;

- you have a strong family history of stones;

- you have already formed multiple stones in one kidney (or stones in both kidneys);

- you have specific findings on stone biochemistry (e.g. raised cystine or uric acid levels); or

- you have anatomical abnormalities that are likely cause more stones to form.

What treatments are available for kidney stones?

Your stone will be managed according to what is best for you, for the stone you have and for the symptoms it is causing you

We usually have a detailed discussion with you about the best way to manage your stone(s). Treatment options range from simple observation with repeat imaging, through minimally-invasive treatments (such as shockwave lithotripsy) to surgical interventions (see below). Open surgery is rarely needed nowadays except for non-functioning kidneys caused by stones, rather than just removing the stone(s), the best treatment is to remove the whole of the kidney, by open surgery or using a "keyhole" approach.

More about open surgery More about the "keyhole" surgery

Small stones in your kidney, found "by chance", may only need treatment if they enlarge or cause symptoms. Active treatment, using one or more of the methods below, is likely to be recommended for stones that are:

- causing troublesome symptoms (especially pain);

- causing blockage to your kidney;

- causing infection (especially when coupled with blockage);

- associated with an anatomical problem that might make further stone formation more likely; or

- large enough that delayed treatment might allow the stone to grow more (requiring more invasive measures, with a risk of incomplete stone clearance)

The options below summarise the treatments your urologist may consider. They can be used singly, or in combination (e.g. you may need a ureteric stent after ureteroscopy, and we often put in a nephrostomy tube after percutaneous stone removal). For patients with more extensive or complex stones, those with abnormal anatomy or those with multiple medical problems, a more “tailor-made” plan is needed; this may mean a major intervention first (e.g. PCNL) followed by a less invasive, second-phase procedure (such as ESWL or flexible uretero-renoscopy) to treat any residual stones.

1. Conservative treatment

Pain relief is the first priority, particularly in the emergency setting. Regular paracetamol is a good painkiller and provides a “baseline” to which anti-inflammatory agents (NSAID) can be added as necessary. Not all patients need hospital admission, even with acute ureteric colic. However, in the presence of infection and kidney blockage, or when there is a risk of impaired kidney function (e.g. in patients with only one kidney, known reduced kidney function, or stones in both ureters at once), admission is needed for urgent, active intervention (see options below).

Small kidney stones that cause no symptoms can be monitored by regular checks with ultrasound or X-rays.

Stones in the ureter may not need treatment, particularly if they are small and close to the bladder (from where they may pass by themselves). We usually recommend active treatment if the stone shows no sign of passing after two to three weeks. Larger stones (more than 6mm in diameter) are less likely to pass spontaneously and your urologist may recommend their removal, especially if your symptoms are difficult to control.

Over the last 10 years, urologists have used “medical expulsive therapy (MET)”; this involves using drugs that relax the muscle of the ureter to speed up stone passage. Recent, large, clinical trials have now shown, however, that there is no benefit from MET and, as a result, we no longer use it.

2. Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL)

ESWL is the treatment most often used for small stones (less than 10mm diameter) in your kidney or upper ureter. Many stones will clear with a single treatment, but you may need two or even three treatments to clear a larger stone. Some types of stone do not respond well to lithotripsy (e.g. cystine stones) and the fragments do not always drain well; as a result, you may need additional surgical treatment. Some patients also suffer ureteric colic (again) as the stone fragments pass.

More about ESWL

If your stone does not respond at all to two successive treatments with ESWL, it is unlikely to fragment with any further treatments and other removal methods should be considered.

ESWL should not be performed in pregnant women, if you have a bleeding tendency or if you are taking blood-thinning agents (e.g. heparin, warfarin or other drugs). It may not be possible in patients who are very overweight because this makes it difficult for the lithotripsy machine to focus accurately on the stone.

3. Ureteric stent insertion

Insertion of a ureteric stent is sometimes done when a stone is blocking the ureter and causing severe pain. It bypasses the blockage, but does not actually treat the stone. Small stones can actually pass around the stent while it is in place; if so, the stent can be removed without any further surgery.

More about ureteric stent insertion

When infection is present behind the stone, stent insertion may be used to help settle the infection. In this situation, we would not treat the stone at the same time, but delay fragmentation until your infection has settled.

We often put a stent into your ureter after rigid ureteroscopy or flexible ureterorenoscopy, to allow the ureter to “recover” from the procedure. Depending whether there are any remaining stone(s), we usually remove the stent under local anaesthetic a week or two after the original procedure. If there are still stones present at that stage, we tend to leave the stent in place for longer; this encourages the ureter to dilate (open up) and makes passing a ureteroscope much easier at a second procedure.

4. Percutaneous nephrostomy tube insertion

When your kidney is blocked by a stone in the ureter and has become infected, we may put a nephrostomy tube directly into your kidney through the skin of your loin. This provides excellent drainage of your kidney, can be done under local anaesthetic and allows the infection to settlewith antibiotics. It is an external tube, so is not as convenient to manage as an internal stent; sometimes we may, later, put a stent through your nephrostomy tube from above down; this is usually done by an interventional radiologist, and means that your nephrostomy can be removed.

More about nephrostomy tube insertion

It is usually better to leave a nephrostomy in place until the surgery to treat your stone – your urologist will discuss what is best for you and for your particular stone(s).

5. Rigid ureteroscopy (URS) & stone fragmentation

Stones in the ureter can be removed or fragmented (broken up) using a laser by rigid ureteroscopy. The advantages of this include the fact that all stones, however hard, succumb to laser energy. However, the disadvantages include the need for hospital admission and a general anaesthetic.

More about rigid ureteroscopy

Despite being “minimally invasive” (i.e. it uses a natural opening & does not require an incision), it carries certain risks, and often involves having a ureteric stent for a short time afterwards; the stent will need a further procedure to remove it, usually under local anaesthetic.

6. Flexible uretero-renoscopy (fURS) & stone fragmentation

Smaller stones in the kidney can be treated directly using a thin flexible telescope passed from your bladder to your kidney. We use a laser to break up the stone(s) and a basket retrieval device to remove the fragments. fURS is a complex surgical procedure which you should discuss with your urologist before you choose to go ahead. Again, it is likely that you will need a temporary stent after the procedure; if you need a second-phase operation (e.g. for one of the larger stone fragments), you may need to keep the stent in for several weeks between procedures; it can only be safely removed when all the stones have been cleared.

7. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL)

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy ("keyhole" removal) is used for large stones in the kidney or upper ureter. It can also be used as a “salvage" treatment if other approaches have failed to break or clear the stone. It is a more major procedure than those listed above. It does, however, allow us to clear larger volumes of stone in a single procedure, and to treat stones in awkward positions that would not be easy either to reach with fURS, or to target with ESWL.

More about percutaneous stone removal

The main disadvantage is a greater risk, particularly of bleeding; this may mean that you need a blood transfusion or additional treatment to stop the bleeding. It is, of course, an important risk (occurring in 1 to 2% of patients); if you have a bleeding tendency or you are taking blood-thinning medications, you may be better advised to consider a phased fURS approach (i.e. several telescopic procedures at intervals) for your stone.

What follow-up do I need afterwards?

If you have had acute ureteric colic, we will usually arrange to see you in outpatients to see whether your stone has passed. If your stone was found "by chance", we will review you with further X-rays or scans, to make sure it does not move or enlarge. We will also review you after any form of active intervention, to be sure that you have recovered as expected, and to arrange further X-rays to see whether your stone has been cleared. If you have stone fragments left behind, you may need further treatment or monitoring.

Regardless of your initial stone burden or treatment, we will advise you about strategies for reducing your risk of further stone formation.

1. General measures to prevent recurrent stone episodes

We normally give you advice about changes to your diet and fluid intake which will reduce the risk of further stone formation.

More about dietary advice for stones

The most important measure is to increase your daily fluid intake. It is best to drink tap water, and you should drink enough to produce a urine output of 2 to 2½ litres (4 to 5 pints) each day. This involves drinking a lot of fluid; it is, therefore, best to drink continuously throughout the day, rather than going from periods of dehydration to drinking lots in one go. There is no need to drink expensive bottled water: tap water is just as good.

It is likely that the levels of natural stone inhibitors in your urine (especially citrate) can be increased by drinking fresh lemon juice in water. This is useful if you have uric acid stones (which are less likely to form in alkaline urine caused by drinking lemon juice) or calcium oxalate stones (because high urinary citrate levels prevent calcium oxalate crystallising).

You should NOT restrict your calcium intake, even if your stone is made out of calcium. Studies have shown that a normal calcium intake actually protects you from future stone formation; a low calcium diet (which is quite difficult to achieve) actually INCREASES your risk of stone formation.

Other general advice to reduce your risk of further stones includes:

- reducing your intake of animal protein (especially meat);

- reducing the amount of refined sugar in your diet; and

- reducing your salt intake.

2. Specific medical treatment for high-risk stone formers

Additional medical treatment may be needed to reduce your risk of further stones if:

- you are at high risk of stone recurrence (e.g. you have cystinuria);

- you have a large stone volume at presentation;

- you have stones in both kidneys; or

- you only have one kidney and it contains stones.

This advice will be guided by biochemical analysis of your stone(s) and by examination of 24-hour urine collections. Specific medical treatments include:

- urinary alkalinisation - with potassium citrate or sodium bicarbonate if you have uric acid stones;

- treatment with thiazide diuretics - if you have a raised calcium level in your urine; or

- treatment with tiopronin or d-penicillamine - if you have cystinuria.

These treatments may need to be continued for a long time. We may also arrange for you to see a nephrologist (renal physician) or other specialist with expertise in stone formation or genetics.

Page dated: March 2024 - Due for review: August 2026