Managing Stones in the Kidney & Ureter

Huge changes in management over 80 years (by the Museum staff)

From long-stay open surgery using large incisions to day-case endoluminal laser "dusting"

When BAUS began 80 years ago, Victor Dix, a Professor of Surgery was said to be a noted expert in the management of ureteric stones, a skill he had honed treating soldiers in the deserts of North Africa in WW2. He removed the stones by open ureterolithotomy, exposing the ureter, slinging it above and below the stone, nthen cutting on to the stone to retrieve it; a major undertaking. Kidney stones were similarly managed by open surgery, sometimes by nephrectomy which was often the only resort for large stones.

When BAUS began 80 years ago, Victor Dix, a Professor of Surgery was said to be a noted expert in the management of ureteric stones, a skill he had honed treating soldiers in the deserts of North Africa in WW2. He removed the stones by open ureterolithotomy, exposing the ureter, slinging it above and below the stone, nthen cutting on to the stone to retrieve it; a major undertaking. Kidney stones were similarly managed by open surgery, sometimes by nephrectomy which was often the only resort for large stones.

I

I n the latter quarter of the 20th century, John Blandy (left) and John Wickham (right) engaged in a surgical rivalry over the best way to remove renal stones - nephrotomy or pyelotomy.

n the latter quarter of the 20th century, John Blandy (left) and John Wickham (right) engaged in a surgical rivalry over the best way to remove renal stones - nephrotomy or pyelotomy.

Blandy used the technique popularised by Gil-Vernet, opening the renal pelvis in a plane very close to its serosa and exposing the stones with tiny malleable copper retractors. Staying close to the renal pelvis was key because it avoided damaging blood vessels directly underneath the parenchyma at the back of the kidney.

Wickham, who had seen various methods of renal cooling in America, cut into the renal tissue to access the calculi. Cooling with ice or infusing inosine intravenously after clamping the renal artery allowed up to an hour of intra-renal surgery. However, a stone that was stuck in a calyceal neck sometimes required removal of the whole upper or lower pole, and sometines even the entire kidney.

Old style right-angled choledochoscope used to retrieve stones during open renal surgery

All of these procedures involved a significant risk of stone recurrence, major morbidity and a prolonged period of hospitalisation.

Stones in the ureter

In 1958, the Italian Enrico Dormia published a paper describing two new instruments, a metal tricep grasper and a basket for extracting ureteric stones. For his initial experiments, he used a ureteric catheter and some guitar strings! This was a great advance but not without danger - blindly pulling out stones could find the ureter coming out too!

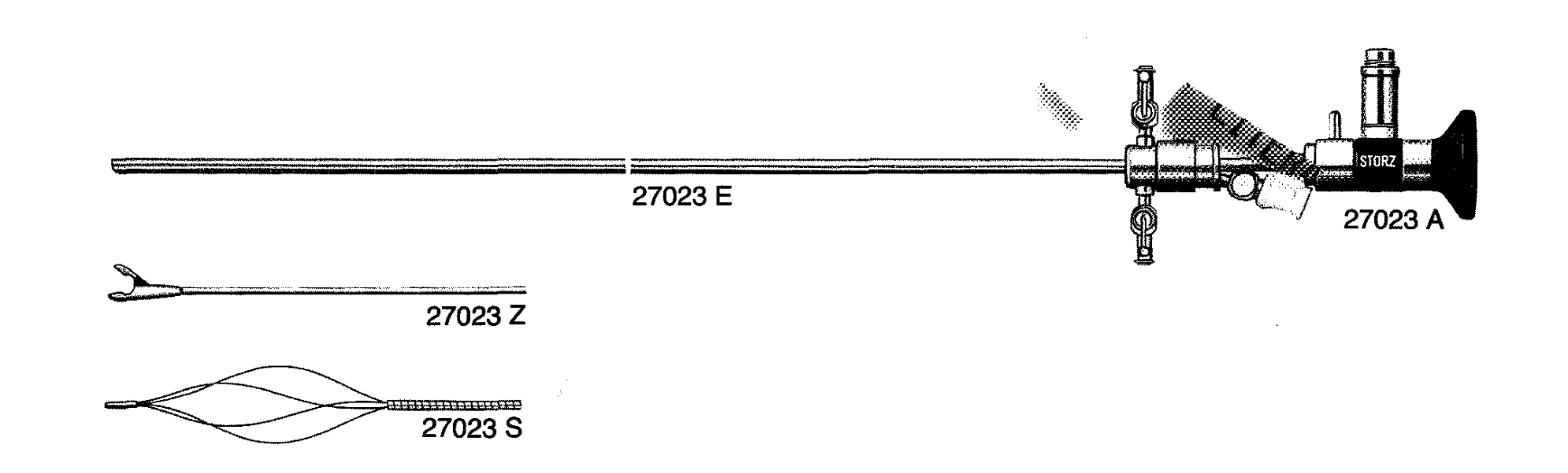

Ureteroscopy was first recorded by Hugh Hampton Young in 1912, when he passed a cystoscope up a hugely dilated ureter. In the 1970’s, Edward Lyon in Chicago used a paediatric cystoscope to manage a distal ureteric stone. Working with instrument makers Richard Wolf, he developed a 12Ch ureteroscope. At the same time, in Spain, Perez-Castro was designing his ureteroscope with the Karl Storz company (see image below). As a result of these advances in instrumentation, ureteric stones could be diagnosed and managed under endoscopic vision.

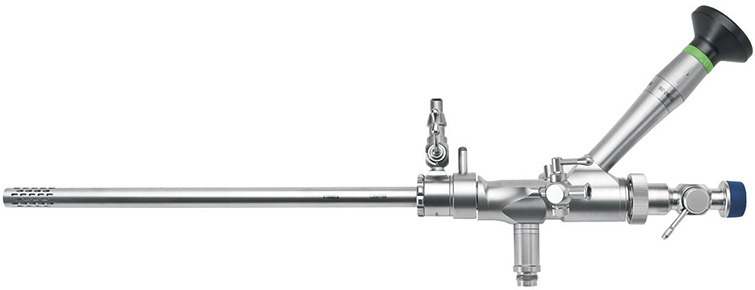

Perez-Castro uretero-renoscope by Karl Storz with Dormia stone extraction basket (and stone forceps)

Some years later, Graham Watson, a urology Fellow working with John Wickham, was experimenting with lasers to fragment stones. In the early 1980’s, he was one of the first surgeons to use a laser to fragment ureteric stones.

Nowadays, laser energy has become first choice for "dusting" stones in the ureter and clearing the majority of calculi in the ureter (and kidney too). This, together with the introduction (and subsequent evolution) of flexible ureteroscopes and ureteric stents, has also made management of stones in the ureter much safer and, often, much easier.

Stones in the kidney

In America during 1941, Earnest Rupel and Robert Brown passed a cystoscope down a nephrostomy tract to remove a stone from a single obstructed kidney. The nephrostomy had been created using a 26Ch catheter that had been placed earlier by open surgery. In 1974, Philip Clark of Leeds was experimenting with ways of carrying out nephroscopy to differentiate between calyceal stones and calcification in the pyramids. In a presentation at the Canadian Urological Association in Ottawa (and in a subsequent paper) he looked forward to the possibility of “renal lithotrites and resectoscopes” in the future. However, in that same year, Fernström and Johansson first carried out a percutaneous renal stone extraction in the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, and published their technique in 1976.

In London, John Wickham and radiology Registrar Mike Kellet began using the same technique, performed in stages. A nephrostomy was placed first then, two days later, a tract into the kidney was dilated to 26Ch. The following day a 21Ch cystoscope was passed into the kidney and the stone(s) removed with a Pfister-Schwartz basket. They presented five cases (four successful) at BAUS in 1980. As techniques and instrumentation improved, it became possible to treat larger stones in the kidney by fragmenting them using electrohydraulic lithotripsy (an underwater electric spark), ultrasound or pneumatic lithotripsy (using a rapidly oscillating metal rod), so that the smaller fragments could be extracted through the nephrostomy track.

Original 24FG nephroscope with offset eyepiece & instrument channel

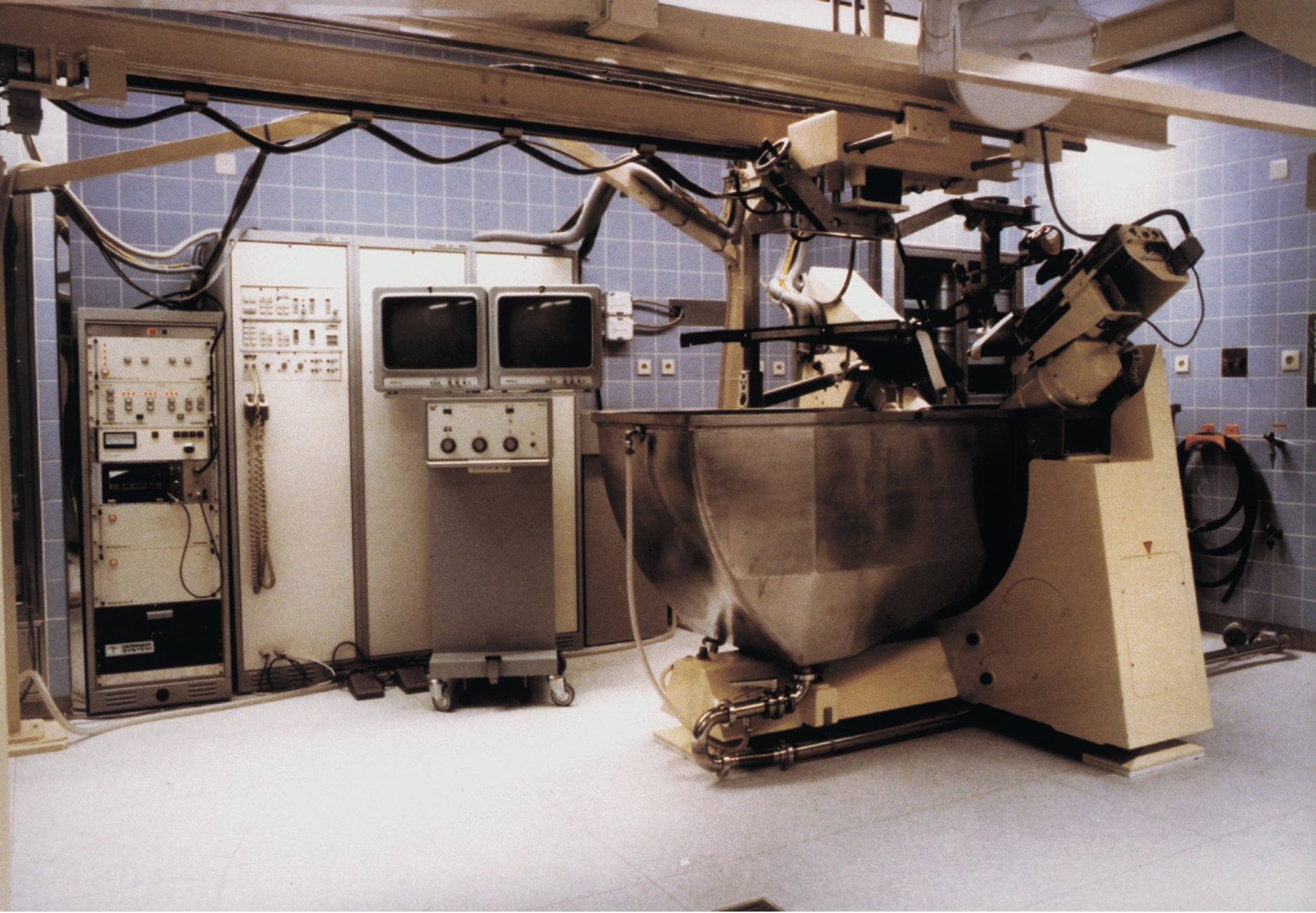

Also in 1980, on 7 February in Munich, Christian Chaussy carried out the first extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL) for a kidney stone. Wickham had been following Chaussy's research since 1978 and tried hard to get one of the huge Dornier lithotripsy machines introduced into the NHS, for which the patients needed a general anaesthetic & immersion in a water bath during treatment. Eventually, he secured one in a private clinic on the understanding that registrars from St Peter’s could train on it and some NHS patients could be treated.

An early Dornier HM1 lithotriptor

After successfully treating 1000 patients in the first year, a further machine (a more advanced Dornier HM4) was bought for St Thomas’s Hospital in London. Subsequent lithotriptor development resulted in more compact machines that did not require a water bath and had less painful shockwave generation, allowing treatment to be performed on a day-case basis using simple painkillers only or intravenous sedation.

In 1987, John Wickham wrote an article for the British Medical Journal titled "The New Surgery" (see link below). In it, he announced minimally-invasive surgery and his vision for the future. The vision was both a reflection of urology’s past and an accurate prediction of its future, as surgery for stones became progressively less invasive and continues to do so. His newly-established, minimally-inasive unit became the gold standard for current endourological practice.

Where are we now?

Improved instrumentation, with flexible ureteroscopes and small calibre nephroscopes, has made upper tract stone removal much safer, and far more effective. Laser energy delivered down small, flexible fibres allows stones to be reduced to fine dust, thereby avoiding the need to extract large, spiky fragments with stone removal devices. The end result, in 2025, is that most patients have their treatments on a day-case or short-stay basis with excellent results and minimal morbidity/mortality - a far cry from the days of long, painful incisions in the loin and several weeks in hospital. Open surgery is now performed in less than 4% of patients with upper tract stones.

Additional Information

Click on any image below to access more detailed information about items & individuals featured above, or click here to go to the main History section of this website for more general history content:

|

Open surgery for stones

|

Lasers in urology

|

Early nephroscopes

|

|

John Wickham biography

|

"The New Surgery" (1987)

|

"Future Developments" (1994)

|

← Back to BAUS 80th Anniversary