18th Century quack or medical pioneer?

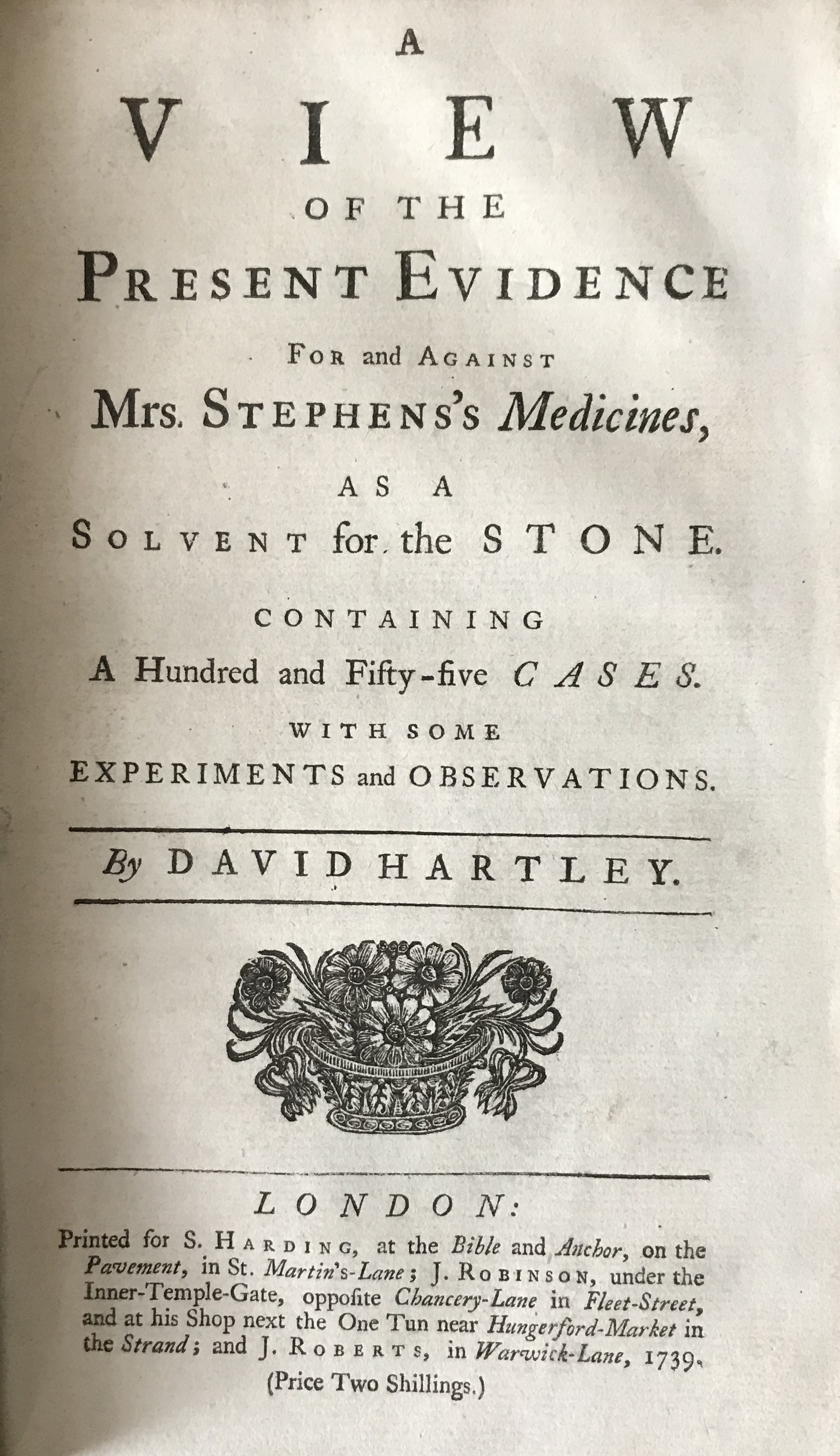

In 1739, Joanna Stephens was paid £5000 by the British Government for a recipe to cure bladder stones; this was a fabulous amount of money at that time, equivalent to around £650,000 today. You can purchase a much cheaper digital copy of the "cure" from Amazon by clicking on the image (top right).

The historical treatment of bladder stone was open lithotomy, an agonising, dangerous operation; thus, any non-surgical alternative to treat stones was eagerly sought. So, when in 1738 an article was published in the Gentleman’s Magazine extolling the benefits of Mrs Stephen’s Cure for the stone, national interest was generated.

The historical treatment of bladder stone was open lithotomy, an agonising, dangerous operation; thus, any non-surgical alternative to treat stones was eagerly sought. So, when in 1738 an article was published in the Gentleman’s Magazine extolling the benefits of Mrs Stephen’s Cure for the stone, national interest was generated.

Stephens offered to sell her recipe to the country for £5000. At first, a private subscription was set up through the Gentleman’s Magazine and, when this only raised £1356 3s, a petition was made to Parliament. A Parliamentary committee was set up and they tested the recipe on four stone sufferers. The patients were examined before and after by a committee of 22 doctors, politicians and scientists and found to be cured. Parliament agreed to pay Joanna Stephens £5000 and she published her recipe in the London Gazette on 16 June 1739.

The powder consisted of egg shells and snails; the decoction of boiled herbs, soap, swines’ cresses, and honey; and the pills, snails, wild carrot seeds, burdock seeds, ashen keys, hips, hawes, soap and honey.

Lithontriptics - medicine to dissolve stones in vivo - had been tried for thousands of years. As chemical knowledge and techniques progressed, more thought was put to their composition and actions. Alexander Marcet subsequently analysed stones and defined six types, lithic acid, oxalate of lime, cystine, calcium carbonate, phosphate of lime and ammonium magnesium phosphate . This may not sound very appetising, nor very scientific, but some of the ingredients, notably the alkaline soap may dissolve urate stones.

. This may not sound very appetising, nor very scientific, but some of the ingredients, notably the alkaline soap may dissolve urate stones.

Joanna Stephens was born in 1692/3 and was said to be the daughter of a “Gentleman of good estate and family in Berkshire”. It is unclear how she came to possess the recipe, which consisted of a pill, a decoction (a solution created by boiling to extract chemicals) and a powder. It was said that, as a young woman, she made remedies that she distributed free of charge to poor people. After the death of a close friend from kidney stones, she devoted herself particularly to remedies against stones. Having discovered, by chance, a recipe for the dissolution of stone in the bladder and kidneys, she began to prepare and distribute it. The evidence for this story is very unclear.

Joanna Stephens has, by many, been relegated to the position of 18th centruy "quack". However, it is possible that her remedy would have worked for some patients and, more importantly, it stimulated the pursuit of chemical analysis of stones which subsequenty formed the basis of modern medical biochemistry. It was also said that she "disappeared" once she had been paid by the government, again indicating she was a quack or trickster. But it appears she merely bought a nice house in Brookgreen, in Hammersmith where she lived to the ripe old age of 82.

She died on 10 November 1774 and was buried a week later. Her death was said to have been brought on by the shock of being robbed in her house earlier that year, on 6 August, by two brothers, Henry and James McAllister.

They were said to have taken four half crowns and three pounds in money, although they were later acquitted at the Old Bailey.

← Back to Famous Clinicians Room