Magic, spirits & herbs

Before the Egyptian and Sumerian civilisations, there were no written records, so what we know about diseases and their treatment during prehistoric times has been gleaned either from archaeological evidence, or from interviews with aboriginals whose lifestyles have not changed for thousands of years.

The land was sparsely populated by nomadic hunter-gatherers occupying seasonal camps in caves or rock shelters where food was plentiful. The average lifespan was 25 to 40 years. It was generally believed that all natural things were controlled by spirits, and that illness was the result of evil spirits, sent either as punishment from the gods or as magic from an enemy.

The land was sparsely populated by nomadic hunter-gatherers occupying seasonal camps in caves or rock shelters where food was plentiful. The average lifespan was 25 to 40 years. It was generally believed that all natural things were controlled by spirits, and that illness was the result of evil spirits, sent either as punishment from the gods or as magic from an enemy.

The "cure" was to drive out the evil spirits; this involved witch doctors or healers (shamans) using ceremonial magic.

Archaeological evidence

Study of human remains suggests that the common diseases in prehistoric times were:

- osteoarthritis (from heavy lifting and carrying)

- microfractures of the spine & spondylosis

- hyperextension and torque injuries of the lower back, often associated with carrying latte stones

- infections and their complications

- rickets

Mummified bodies have revealed ingested plants and seeds from the Palaeolithic era (60,000 years ago) onwards. These include yarrow (as an astringent to stop bleeding), mallow (as a laxative), rosemary, digitalis, morphine (extracted from seeds as a painkiller), snakeroot (as a mild sedative) and birch polypore fungus (as a laxative).

Mummified bodies have revealed ingested plants and seeds from the Palaeolithic era (60,000 years ago) onwards. These include yarrow (as an astringent to stop bleeding), mallow (as a laxative), rosemary, digitalis, morphine (extracted from seeds as a painkiller), snakeroot (as a mild sedative) and birch polypore fungus (as a laxative).

Some Stone Age skulls have been found with holes cut into them and, in some, there is evidence of the bone "growing back", implying that the individual survived the procedure. This practice, known as trepanning (pictured upper right), has been in use for thousands of years to treat epilepsy, headaches, mental illness and assumed demonic possession, although it may also have been performed as part of a ritual.

More about the practice of trepanning

Archaeological evidence has been found of geophagy (eating earths & clays). This may have been prompted by watching animals eat earth, either to get essential minerals or when they are unwell.

Evidence from aboriginals

Some aboriginals still practise lifestyles that have not changed for thousands of years. In the late 19th century, a number of interviews were carried out with aboriginal groups in an attempt to understand some prehistoric relics being discovered at that time.

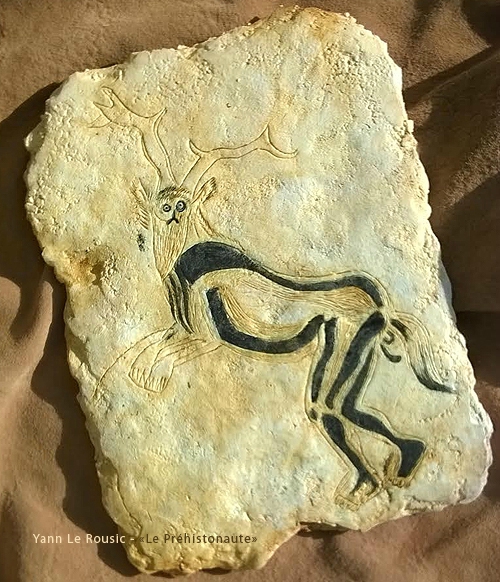

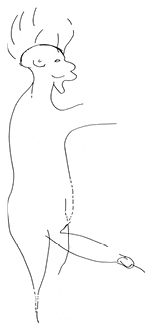

Cave paintings can provide information about the lifestyle of prehistoric nomads. A prime example is the Grottes des Trois-Frères in southwestern France where the cave art dates back at least 13,000 years. There are numerous engravings in the three caves, but The Sorcerer (pictured middle right) is of particular interest in that it may represent a healer with a deer-mask, worn to frighten away the demons causing illness (or simply to impress the patient!).

Cave paintings can provide information about the lifestyle of prehistoric nomads. A prime example is the Grottes des Trois-Frères in southwestern France where the cave art dates back at least 13,000 years. There are numerous engravings in the three caves, but The Sorcerer (pictured middle right) is of particular interest in that it may represent a healer with a deer-mask, worn to frighten away the demons causing illness (or simply to impress the patient!).

More about the Grottes des Trois-Frère

Some present-day aboriginals still treat fractures using wet clay which then hardens to give support to the limb in the same way as a plaster cast does. Hunter-gatherers were, of course, prone to trauma and fractures because their lifestyle involved significant personal risk whilst hunting and killing large animals.

Prehistoric urology

Although we have no archaeological evidence of urological disease, prehistoric cave paintings of the penis have been found dating back to the Upper Palaeolithic period (12,000 to 40,000 BC). They suggest an awareness of erection, copulation, ejaculation (pictured lower right) and orgasm.

Read more about the "Prehistoric penis"

Indirect evidence exists that foreskin retraction and/or circumcision was also performed, and a detailed analysis suggests that other decorative rituals (tattooing, piercing, and scarification of the penis) took place, possibly as group recognition strategies, especially during the Upper Magdalenian period (11,000 to 12,700 BC).

← Back to Time Corridor