"The age of agony"

Surgery, as a specialty in its own right, finally became established as the 19th century began, with the foundation of the Royal College of Surgeons of England in 1800.

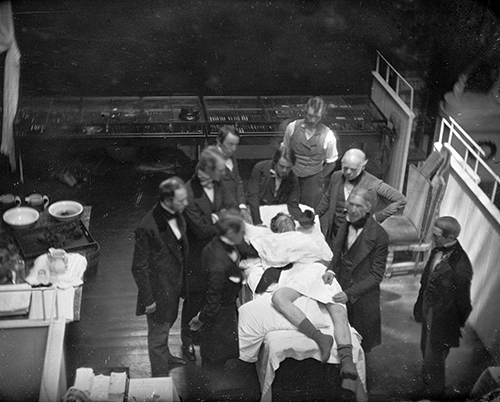

At this point in time, up to 80% of all surgical patients died, usually in the post-operative period, and surgeons were still not considered "proper" doctors. The most important requirements for a surgeon were speed and dexterity. The renowned surgeon Robert Liston (pictured upper right) once amputated a leg in 2½ minutes from first incision to skin closure. Operations were carried out in an operating "theatre", aptly named so that the surgeon could put on a show for the audience: Liston often began his procedures by encouraging his audience to "time me, gentlemen".

At this point in time, up to 80% of all surgical patients died, usually in the post-operative period, and surgeons were still not considered "proper" doctors. The most important requirements for a surgeon were speed and dexterity. The renowned surgeon Robert Liston (pictured upper right) once amputated a leg in 2½ minutes from first incision to skin closure. Operations were carried out in an operating "theatre", aptly named so that the surgeon could put on a show for the audience: Liston often began his procedures by encouraging his audience to "time me, gentlemen".

Procedures were performed without anaesthetic, and with no regard for sterility or blood loss. Until these factors could be addressed, surgery remained a hazardous undertaking for the patient ... but, by the end of the 19th century, all of these factors would be resolved.

The introduction of anaesthesia

Nitrous oxide ("laughing gas") was isolated in 1772 by Joseph Priestley, and its pain-relieving properties were well-known. The gas was frequently used for public entertainment. It was, however, dentists who popularised its use. Eventually, it was (and still is) administered to maintain safe anaesthesia in most surgical patients.

Nitrous oxide ("laughing gas") was isolated in 1772 by Joseph Priestley, and its pain-relieving properties were well-known. The gas was frequently used for public entertainment. It was, however, dentists who popularised its use. Eventually, it was (and still is) administered to maintain safe anaesthesia in most surgical patients.

In 1846, William Morton made history by administering the first ether anaesthetic to a patient at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, USA (reconstruction pictured middle right, with Bigelow as one of the surgeons).

Read more about William Morton

In 1847, James Young Simpson of Edinburgh became the first person to administer a chloroform anaesthetic - to himself. It soon replaced ether as the anaesthetic agent of choice but was later found to cause heart and liver toxicity, and was withdrawn.

Read more about James Young Simpson

It was only when it became possible to anaesthetise patients safely and reliably, that the surgeon's repertoire was able to expand rapidly.

The introduction of sterile operating conditions

Until the mid-19th century, it was still thought that infections spread through the atmosphere as a noxious form of bad air called "miasma". John Snow, whilst investigating the catastrophic 1854 cholera outbreak in London, showed that a single water pump was the source of the infection, and thereby took a major step forward in vindicating the "germ theory" supported by Louis Pasteur. Snow, incidentally, also administered ether and chloroform anaesthetics to his patients; amongst their number was Queen Victoria, who received treatment during labour.

After surgery, instruments were never sterilised, surgeons operated whilst wearing clothes contaminated from previous operations, and operating theatres were never cleaned. It is no surprise that so many patients died of infection.

After surgery, instruments were never sterilised, surgeons operated whilst wearing clothes contaminated from previous operations, and operating theatres were never cleaned. It is no surprise that so many patients died of infection.

In 1867, Joseph Lister showed definitively that "germs" spread infection, and recommended the routine use of carbolic acid steam spray (pictured lower right) as an antiseptic during surgery. This resulted in post-operative mortality dropping from 46% to 15% within three years. Unfortunately, carbolic acid irritated the skin, eyes and lungs of staff. However, in 1889, Lister showed that sterilisation of clothes, hands and instruments gave even better results, with complete clearance of "germs" (asepsis).

Read more about Joseph Lister & asepsis

Now that surgeons had a sterile operating theatre environment, surgery was changed for ever.

The reduction of blood loss

Skilled surgeons (and their assistants) knew how to compress major blood vessels before their first incision; thereafter, it was up to the surgeon to tie off any blood vessels as quickly as possible. Despite this, blood loss was often considerable. It was usually soaked up by sawdust on the floor, and was swept away at the end of each surgical session.

In 1900, the discovery of the ABO blood groups by the Austrian physician and immunologist, Karl Landsteiner, paved the way for blood transfusion and replacement of blood lost during surgery, although it came too late for 19th century surgeons.

Urology in the 19th century

For too long, urologists had been confined to "cutting for stone" or treating urethral strictures, but all that changed with the development of a workable cystoscope. Early cystoscopes by Philipp Bozzini prompted a development process that lasted until the end of the 19th century, when Max Nitze produced a cystoscope with a light source which was in the bladder but did not need cooling.

This, in turn, prompted urologists to start treating prostate enlargement endoscopically, either by incision/resection or by punch.

But it was only in the middle of the 20th century that urological endoscopy came into its own with Karl Storz's development of the Hopkins rod lens system. As a result of Harold Hopkins's pioneering work, urologists can now see inside most urinary organs and body cavities.

More about Harold Hopkins's pioneering

← Back to Time Corridor